“At a certain point we’re gonna have to build up some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because the technology is just gonna get better and better and better and better. And it’s gonna get easier and easier and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by by people who do not love us but want our money.”

— David Foster Wallace

About a year ago, I wrote an essay predicting the end of our extremely online era. Much to my surprise and horror, it went viral1.

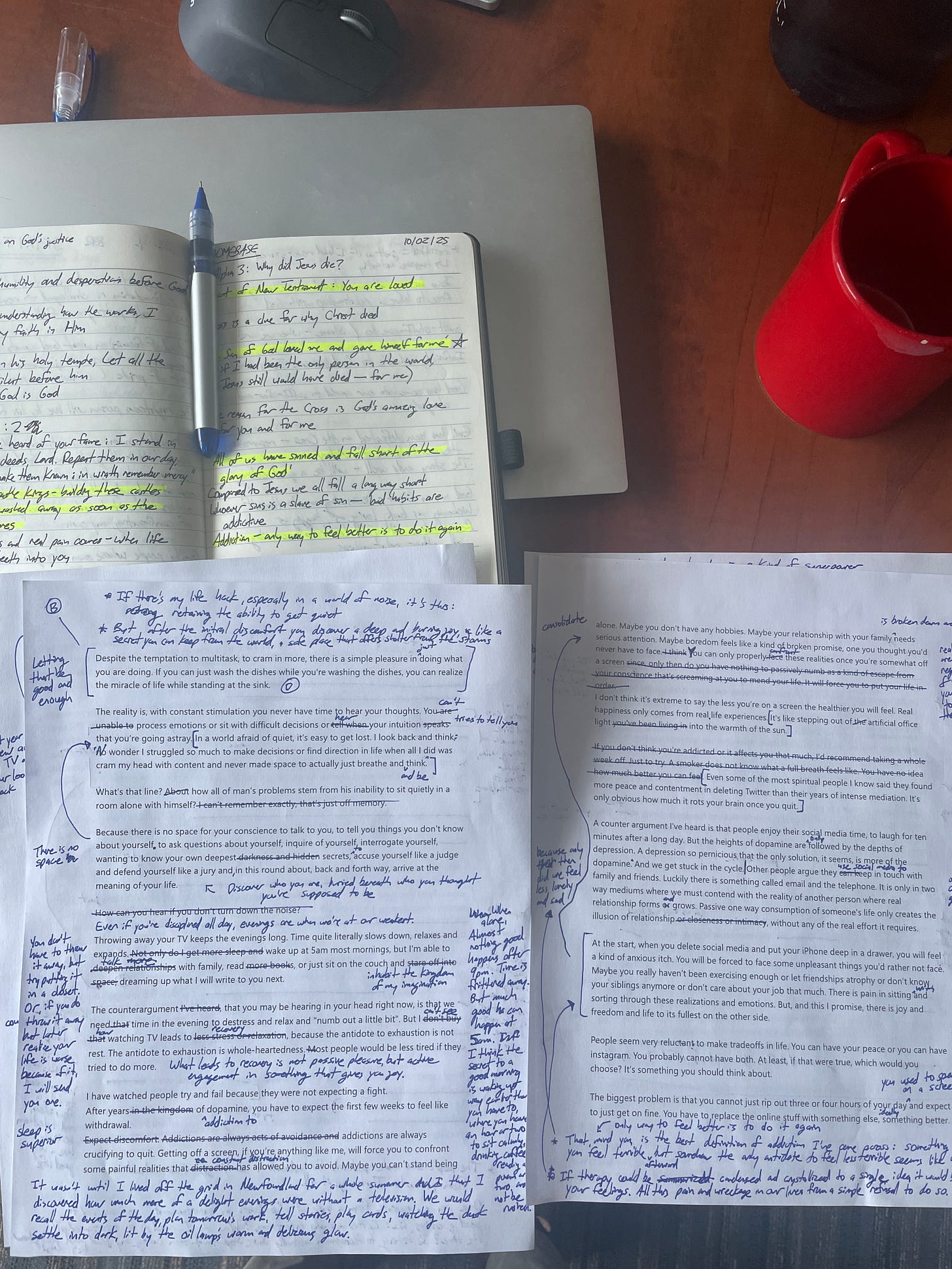

I still stand behind the piece, but I realized that it’s more of an abstract argument than a practical guide. It’s missing next steps on what being less extremely online looks like in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence. That’s what I want to talk about in this essay2.

The surprising thing about the essay going viral was the fact that it’s not very good writing. Nowhere close to my best work. I wrote it in half-hour intervals over the span of four days, sitting on the floor of a cabin on the coast of Newfoundland, my laptop on life support from a solar panel battery. The finished product was mostly a first draft.

When people ask me, I say the same thing: its popularity was not from the quality of the writing but the resonance of the topic. It gestured toward a subconscious yearning we all seem to share. This urge to be less online. To be less performative, less see-through, less concerned with what others think of how we live, and more deeply involved and intimate with our own real local lives.

This longing is evident. Everywhere essays are going viral on how to stop doomscrolling on your gross little phone and instead live an intellectually rich life. How David Foster-Wallace predicted it all, this strange post-literate society we now find ourselves in, where we’re all lonely because we’re overconnected, and to cope everyone is numbing out. Nowadays, people literally just want to do things.

We live in a culture of watchers and appearers, of watchers and approvers, a culture where it feels distinctively hard to be a real human being. It’s like some sort of Orwellian nightmare, but worse, since we are being watched, but we have also employed ourselves as the watchers, as big brother, looking in at a projected image of everyone’s life, which isn’t that real but we, for some reason, pretend it is.

The other night, I got a flat tire on my bike, the fourth this year, and I had to take the city bus home in the dark. And as I stood on the bus, being rocked back and forth by potholes, I saw a girl across from me, Lebanese maybe, big bulky plastic headphones on, coat stuffed up to her ears, flicking through videos with an almost familiar ferocity. Videos of tall white women with perfect makeup, tall white women in sparkling red dresses, tall white women on beaches or in Italy. I saw a guy beside me with plastic headphones the size of arctic earmuffs, watching call of duty gameplay, while scrolling through videos about Trump and missile strikes, while changing videos every few seconds. And I saw another guy on the bus, beside the hypothetically Lebanese girl, watching a videos of a chef pulling pizzas out of a wood-fired oven, pizzas with genoa salami and sweet pepper and fennel, pizzas with prosciutto and arugula, pizzas with sausage and wild mushrooms, pizzas glistening, bewitched to a dark gold, while he pulled a second hard boiled egg out of a big crinkled Ziploc bag and began to peel it, without really looking, since he was watching his videos, fumbling his phone on his knees, surfing his phone across his knees, trying to hold the shell bits in one hand, but not really paying attention, since he was watching his videos, eggs shells cracking, egg shells splitting, egg shells falling all over floor. And I thought to myself, “This must be a metaphor or something”. And I looked down the dark bus, lit up by a blue glow, and everyone was doing the same thing. Necks bent at forty-five degrees, postured to the palm of their hand, lost in a world that is entirely not their own.

I couldn’t help but come to the conviction, right there on the bus, that one of the most important questions modern man must ask himself is how much time he is willing to spend being passively entertained.

To reduce phone use, there are a few tactical things like deleting social media and email apps, deciding not to scroll during daylight, setting the screen to black and white, leaving it buried in a drawer or in another room, or even more extreme measures like downgrading to a dumb phone. But the reality is that without addressing the deeper, more metaphysical angst that drives this addiction, no tactics will make that much of a difference.

We are drowning in a river of short-form video. Where the allure isn’t even the content but the abundance, the infinitude of the flow. As the cultural conversation is dominated by what is fast and loud and immediately engaging, because those are the qualities screens reward, we lose the capacity to think in paragraphs, to think hard about the same thing for half an hour, to practice any kind of sustained attention. The ideas that resist compression are forgotten, cast aside, as everything has to be in bullet points, stripped of all excess verbiage. The faster things go, the more immersed we are in the flow, addicted to the speed, unwilling to grapple with the slowness of the real world around us, the more we forget to feed the part of ourselves that likes quiet, that can live in quiet. That deprivation makes itself felt in the body as a kind of dread.

Screens are reached at, mostly, as an escape. An escape from boredom, from anxiety, from an abating loneliness. Maybe, an escape from ourselves. But instead of causing consolation, screens only make us feel more distant and disconnected and lonely, as an apathy sets in that is increasingly abstract, a kind of stomach-level sadness3.

Yet the worst part, the part that can only be described as sinister, is that the only cure seems like more.

And so a sense of lostness plants in your gut. And the depression thickens. And the loneliness languishes into something with the promise of permanence, something you think you’ll just have to put up with for the rest of your life.

This, mind you, is the best definition of addiction I’ve come across: something that makes you feel terrible, but the only way to feel better, it seems, is to do it again.

I don’t think this feeling is an accident. It’s your conscience, whatever divine spark or higher knowing that is within, sensing it is making you sick, trying to tell you, some days screaming at you, to stop. Meanwhile, Mark Zuckerberg is boasting about AI increasing advertising efficiency, meaning they are using more advanced technology to abuse our attention spans and celebrating it as if it is somehow a good thing.

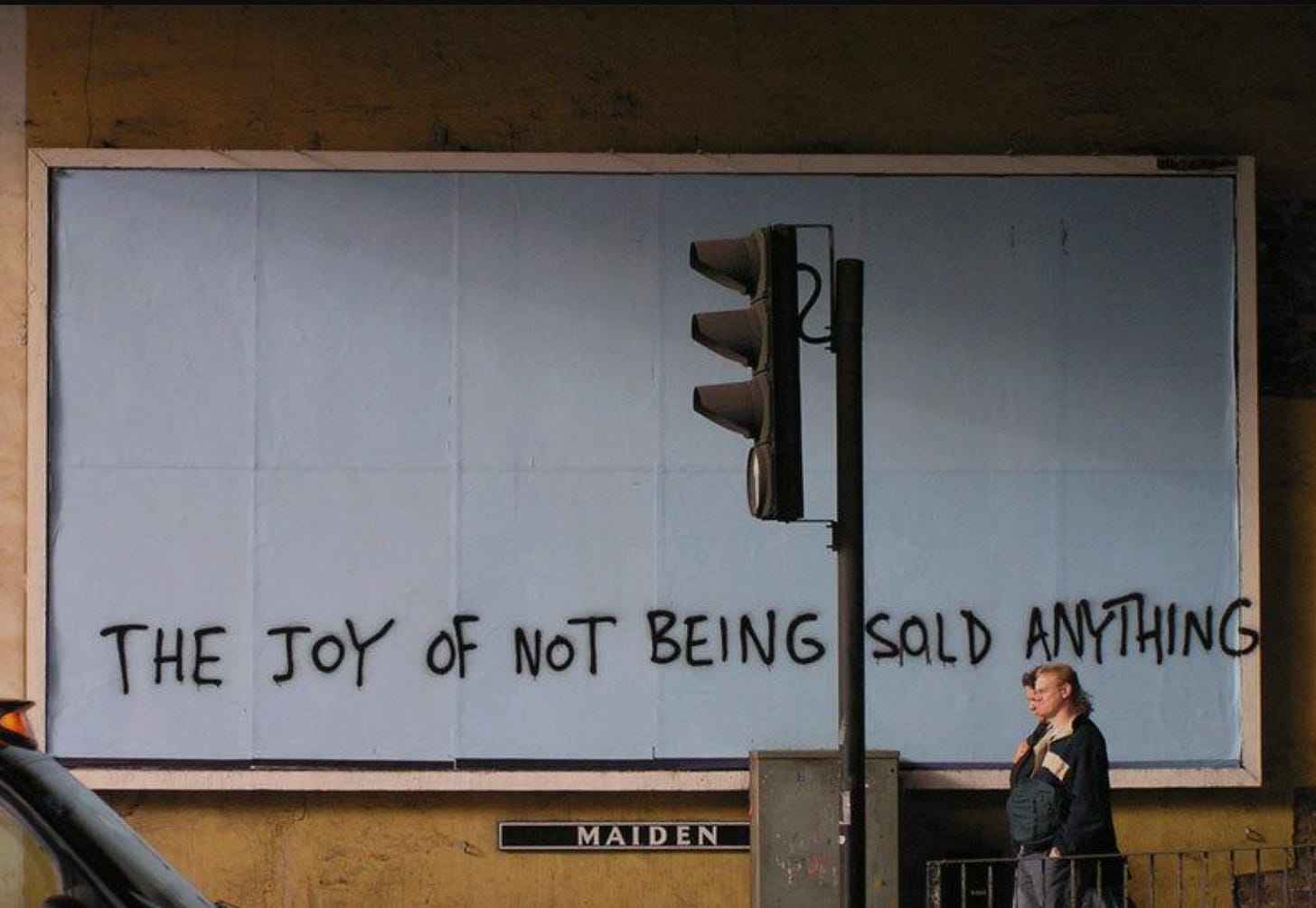

On his regular rants about ‘the Facebook,’ an old business professor I had in Navarra used to say, in his velvet Spanish accent, “If there’s no price, you are the price.” Entertainment’s main goal is not to entertain but to keep you so hooked, so riveted, that you can’t tear yourself away so advertisers can advertise. To create an anxiety that only promises relief by purchase. It’s a system that reduces the nobility of man to a cog in the capitalist machine, a unit of utility, something to sell to.

The goal isn’t entertainment. The goal isn’t even distraction. The goal is addiction4.

There was a Jesuit preacher, Anthony de Mello, who said if you’re suffering but not willing to do anything about it, you need to suffer more. Suffer until you get sick of your suffering. Which sounds harsh, but it’s true. The transformative moments in my life only came when the pain of staying the same finally became greater than the pain of changing. It wasn’t courage, perse, but a recognition of the cost of inaction.

My life today, I would say, is full of good things. I work a full-time job and write essays and read the Bible every morning, plus a few long and difficult books every month. I run and cycle and lift weights and train BJJ and serve at my church and volunteer at community events and lead a study group on Thursday nights. I bake bread and try new recipes and go on long meandering walks and get lost in the woods and stop by the farmers market early every Saturday morning and grow herbs and vegetables. I call family most days and have friends over for coffee and breakfasts and dinners most weeks. Sometimes I shoot my bow and go on long hiking and portaging trips and build wooden things here and there.

As I was thinking about this essay, sitting at my kitchen table with a coffee early in the morning, waiting on the sun, I wanted to take that paragraph out because I thought it sounded boasty and would make people not like me. But the point is not about my life, but that you can get an astonishing amount done when you throw away your TV and get off your phone. Not that getting things done is the purpose of life, but rather that there are so many cool and interesting things worth doing.

Most of a good life is simply refusing to do what is bad.

I have no social media apps, not even Substack, follow basically no news, listen to zero podcasts, and don’t have any streaming services. My information diet comes almost entirely from books. This is partly because I am audacious with the amount I want to read and the only way I can accomplish this is if I cut everything else out. But the real reason is because the flood of information on the internet made me feel anxious and incapable and directionless and overwhelmed. So I stopped.

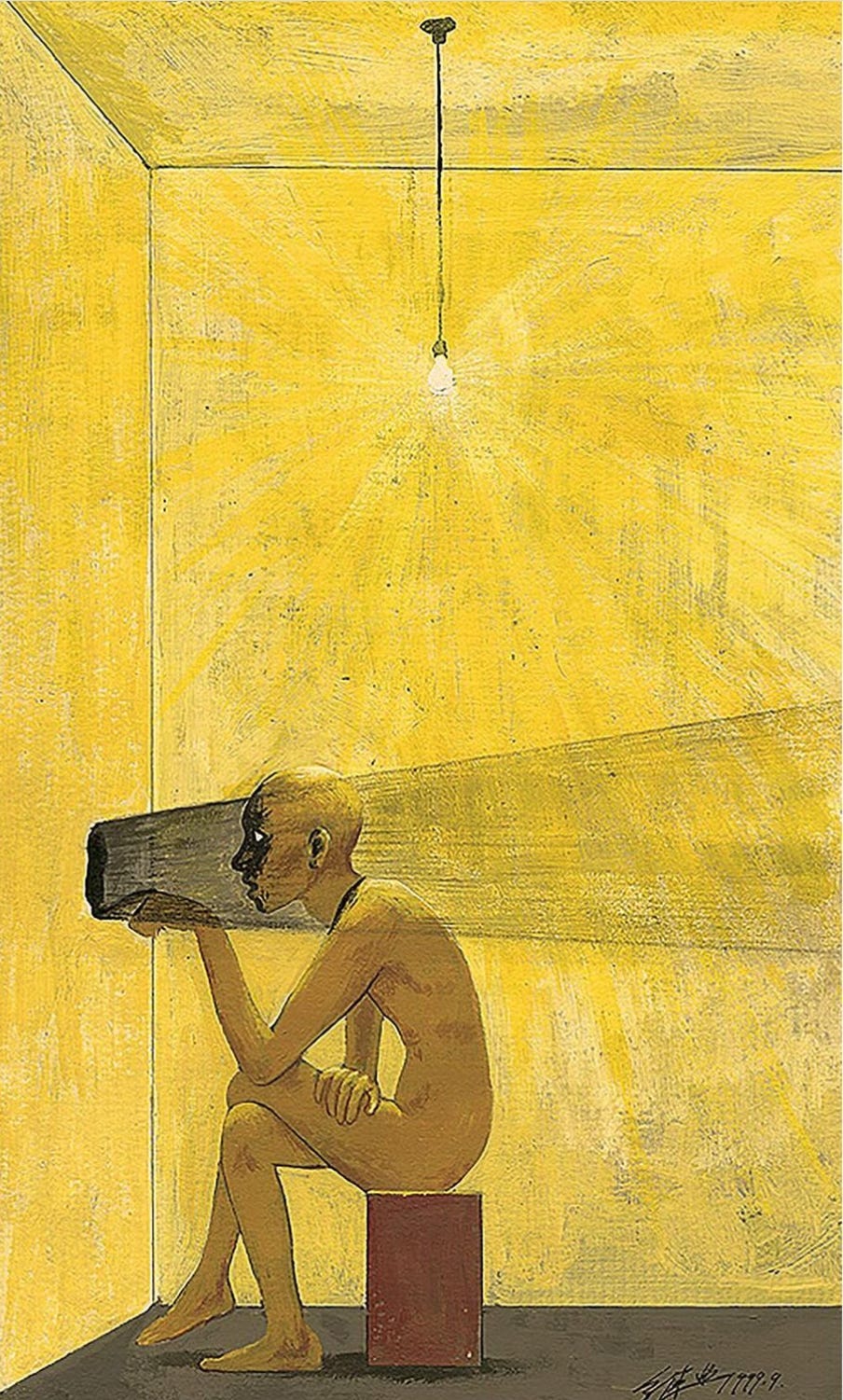

With constant stimulation, you never have time to hear your thoughts or feel your feelings. In a world afraid of quiet, it is easy to get lost. Isn’t there a line about that? About how all of man’s problems stem from his inability to sit quietly in a room alone with himself?

Because there is no space for your conscience to talk to you, to tell you things you don’t know about yourself. There is no space to ask questions about yourself, inquire of yourself, interrogate yourself, wanting to know your own deepest secrets, the things you dislike so much you don’t even think about anymore. There is no space to accuse yourself like a judge and defend yourself like a jury and, in this roundabout, back-and-forth way, arrive at the meaning of your life.

I have watched people try and fail because they were not expecting a fight.

And that’s the thing: this is a fight. It has to be. After years stuck in the spin-cycle of dopamine, you have to expect the first few weeks to feel like withdrawal. Addictions are always crucifying to quit.

At the start, when you delete social media and throw away your TV and put your iPhone deep in a drawer, you will feel an anxious itch, a habitual twitch to check notifications. Getting off a screen, if you’re anything like me, will force you to confront some painful realities that constant distraction has allowed you to avoid. You will be forced to face some unpleasant things you’d rather not face. Maybe you can’t stand being alone. Maybe you don’t have any hobbies. Maybe you let your friendships atrophy, or haven’t had a real conversation with your brother in years, or don’t actually care about your job that much. Maybe boredom feels like a kind of broken promise, one you thought you’d never have to face.

There is pain in sitting and sorting through these emotions. But, and this I promise, there is joy and freedom and life to its fullest on the other side. Not a fake, superficial happiness but a nice, mild, slow-burning rapture, one that feels like a secret you can keep from the world.

I don’t think it’s extreme to say the less you’re on a screen the happier and healthier you will feel. It’s like stepping out of artificial office light into the warmth of the sun. Even some of the most spiritual people I know said they found more peace from deleting Twitter than from years of intense meditation.

People seem very reluctant to make tradeoffs in life. You can have your peace or you can have instagram. You probably cannot have both. At least, if that were true, which would you choose? It’s something worth thinking about.

People argue they use social media to keep in touch with family and friends. Luckily, there is something called email and the telephone. It is only in two-way mediums, where we must contend with the reality of another person, that real relationship forms and grows. Passive one-way consumption of someone’s life only creates the illusion of relationship, without any of the real effort it requires. As if we can have all of the closeness with none of the cost.

I tend to think if someone isn’t important enough for me to actively keep in touch with (take ten seconds to send a text!), they cannot be important enough to passively keep tabs on. There’s also the fact that social media isn’t really used as a social network, but as a way to watch videos made by strangers. Social media isn’t even social anymore5.

The biggest problem is that you cannot just rip out three or four hours of your day you used to spend on a screen and expect to get along fine. You have to replace the online stuff with something else. Ideally, something better.

A few suggestions:

Read a book. You can read more than you think and it’s worth it to try. If you’re a seasoned reader, try something long and difficult, something that stretches you. Don Quixote, War and Peace, or The Count of Monte Cristo are all excellent. Or, if you’re feeling really adventurous, the Bible. I’ve learned that reading is an endurance sport. The first time I tried to seriously read again, it felt like the first time I went for a run: awkward and painful and shorter than I would have hoped. But with love and patience, it grows. I would not recommend a new runner to run a marathon, nor a new reader to pick up War and Peace. Just read. Read anything. Read fairy tales, read instruction manuals, read Calvin and Hobbes. Read what you love until you love to read6.

Make something. It can be bad. But try making something. Choose something useful and worth doing. As you shape it, it will shape you. Carve a kitchen spoon, reupholster a chair, make a bookshelf, or a side table. Pick up a dresser off the side of the road and refinish it. These things aren’t that hard and it’s worth it to try.

Draw or paint. By trying to draw something, you realize that reality has a surprising amount of detail. Most goes unnoticed. Much of drawing is staring at one thing for a very long time, until it comes alive. Writing is the same.

Enjoy music. Stretch out on the couch and listen to a whole album, start to finish, without doing anything else but listening.

Get to know your neighbours. Everyone wants community, but no one wants to talk to their neighbour. The Portuguese woman who smokes cigarettes on the street corner every morning, the old guy who’s always out in his garden on his hands and knees, the grouchy man with the smiling golden retriever. “Online community” is an oxymoron. Smooth and shiny frictionless Zoom rooms where everyone agrees with everything you say is not only inhuman, it’s boring. It is only the diversity that exists in community, the people who are not like us, that makes it real and true and human.

Stare off into space. When’s the last time you were bored? When you watched clouds pass and saw their shapes, dogs and castles and battleships? When’s the last time you looked at the stars? This kind of idle, wandering time will also make you more creative. Much of creativity comes from the ability to stare at a wall for extended periods.

Go outside. I think one of the reasons we have grown distant from the divine and distant from ourselves is because we are so removed from the natural world. Most of my problems are solved, or start to solve themselves, when I touch grass.

Write letters. I read somewhere that Victorians used to spend 1-3 hours a night reading and replying to letters. There is a certain feeling to writing at length, where you can structure your thoughts and articulate feelings and develop a level of detail, that is hard to replace. Plus, people are delighted to receive a letter in the mail.

Host dinners. Everyone is as busy as they’ve ever been, but everyone eats dinner.

Sleep. Going to bed before 9pm for a full night’s rest makes you feel like royalty.

There is something simple and good about a more analog existence. An alluring quality that cannot be explained away. Playing cards after dinner instead of watching TV. Reading on crisp autumn afternoons instead of mindlessly scrolling. Filling your home with books and journals and pens and stamps, not LED things that beep at you.

If you are immune to boredom, if you can get drunk staring into the flames of a fire, or lost in reverie walking by yellow-lit windows, or experience a secret pleasure from staring into space, if you can be by yourself but not lonely, simply alone, then you’ve got it. You have found the sword with which the world becomes your oyster.

As you pull yourself away, as the chains you never saw come crashing to the floor, you learn things. You learn books can tell you things about yourself you don’t know. You learn concentrating on anything is very hard work. You learn what you pay attention to is the job of a lifetime, a job that never ends, a job that quite literally shapes your life because all your life is, you realize, is a story you tell yourself about living.

Inside each of us is something infinite, something eternal, something that someone else can only see a tiny fraction of, even if we spend a lifetime trying to show them. And even if you tried to explain, all this inside you, all that flashes through you, to me, it’s just words. Clumsy words that confine you, clumsy words that grope like a blind man in the dark, knocking over furniture, for the shape, even just the outline, of something fast and fractaled and huge and hopelessly interconnected.

There is so much inside that we can never show another. Because we know this, because we know what people see is never us, but only a part, a tiny and inadequate part, we expend so much energy trying to manage the part that they do see. That will probably never change. We will probably spend our lives being squeezed through a tiny keyhole, and trying to squeeze others through tiny keyholes.

But if there is any way, any hope, of feeling seen it will not be found on a screen but in the real relationships we find ourselves in. Those difficult, lumpy, sometimes annoying things that take constant work and care and attention to keep alive.

Only through the discipline of tending to the relationships that have been placed in our lives, like they’re a garden, like they’re an infant in need of our care, can we begin to poke our fingers through the mask that the other wears and see the broken and hidden things that wake compassion, that make our broken and hidden things seem not so broken and not so in need of being hidden.

That’s the only place, really, where love can grow: in between the cracks in the mask.

Real heroism is not found in the headlines but is only the result of minutes, hours, weeks, and years of exercising a careful and judicious sincerity, often with no one there to see or applaud. This really important kind of freedom involves discipline, doing what is difficult, being obedient to that still, small voice inside your head that knows exactly what you must do and exactly when you’re not doing it.

At the end of the day, the question everyone must answer is how much they want their life to be their own.

It is already late enough.

Write you again soon,

Essays like this take 30-40 hours of work. If you’d like to support my writing and place a vote for a world where I continue to write ambitiously, consider becoming a patron:

If cost is an obstacle, but you’d still like access to all my writing, send me a message and I can make a discount (or a free pass). I don’t want money to be the reason you can’t take part.

Or, you can contribute in a smaller way and buy me a coffee.

Related reading:

Almost every day, I get a message from someone saying they’ve deleted social media or are gradually disconnecting from offline, and how fulfilling the shift feels. “Like my soul is coming back to my body when I wasn’t even aware it was missing.”

Over the last year and a half, it’s been hundreds of people. Perhaps a thousand.

The extremely online era, dare I say it, is at the beginning of the end.

One of my grievances with modern writers is that they have become very good at tearing things down, talking about the badness of everything, telling you how broken our world is, without making an effort to build anything back in its place. Perhaps because it’s complicated and they don’t have the answers, fair enough, but perhaps because it sounds much more literary and sophisticated to be cynical and sharp. It’s also much easier. Whereas to talk about ways of redeeming what is broken, how light will overcome the darkness, how love has not abandoned us, to try to apply CPR to what is human and magical, sounds sentimental and naïve.

If we’re taking a cultural pulse, the widespread feeling of apathy explains why essays on agency, the capacity to act and do stuff, are so popular.

Ted Gioia, The State of the Culture.

From Derek Thompson: “Meta cannot possibly be a social media monopoly, Meta said, because it is not really a social media company... More than 80 percent of time spent on Facebook and more than 90 percent of time spent on Instagram is spent watching videos... A majority of time spent on both apps is watching videos, increasingly short-form videos that are “unconnected”—i.e., not from a friend or followed account—and recommended by AI-powered algorithms.”

A Guide to Surviving the Age of Post-Literacy: How to raise (or become) a reader: “So find a good book, and begin. Read daily and for sustained intervals, bathing your mind in long and beautiful or intelligent text. Read alone. Read to your children. Read without ceasing. The future of society might depend on it.”

Tommy, what the hell. This is my favorite thing you’ve ever written. I’m inspired, liberated, panicked, and of course, ashamed of my doom scrolling even tho it’s “not as bad as most people.” This is what I actually tell myself! Ok I gotta go read my book. Bye.

I have a question for you-what are your thoughts on if it needs to be all or nothing? I love your essay but was thinking it might have some real rules that have worked for you around screens or social media time. I have really enjoyed my social media detoxes, but haven’t yet pulled the plug entirely. I don’t know if it’s possible to straddle both worlds so to speak but I think it’s a challenge we all face- wanting more analog and peace, but also faced with the reality that we live in a technology-driven world. I would like discipline to have an 80 percent analog and 20 percent digital life but haven’t found the strategies and rules to make it happen. Your essay did give me lots of food for thought though…thanks so much