When I returned home in August after my time on the East Coast, I decided to build a wood shed. Despite being somewhat confounded by the fact that I had no clue how.

Over the summer, I had helped build a deck and a set of stairs, but I was always the assistant, not responsible for planning the construction or procuring the materials. I wanted to test what I could do on my own.

It's almost impossible to appreciate the amount of care that goes into making something functional and beautiful until you try to make it yourself. Reality has a surprising amount of detail.

There was also a nagging necessity1.

This will be my first full winter at the cottage. Besides a few electric baseboards, the entire cabin is heated by a single wood-burning stove in the main room. We had a bush cord of hardwood logs delivered, dogpiled in a hulking mass on our back lawn, plus a cord or two left over from last year, and needed a large and dry place to store it. Before, the wood was tossed in a muddy gap between two sheds, covered in a sheet of blue plastic. But now, we had much more wood and, without any surrounding structure, it could only be stacked so high. Not to mention, I despise plastic tarps2.

For anyone handy, building a small wood shed is a mere trifle. But, for most of my life, I'd never hammered or screwed or sawed anything. I couldn't hang a picture, let alone build a free-standing structure. As a kid on Christmas morning, I remember getting my older sister to put together my new Star Wars Lego set. I was only interested in playing with it—more an engineer of stories than spaceships.

So, electing to build a woodshed with very basic carpentry skills and a few old tools was intimidating. Especially with a few hundred dollars of materials and our winter heat source at risk, there were real stakes. I wasn't sure if it could be successfully finished without any major follies or fatal flaws. Really, I wasn't sure if it could be finished at all. But, courting failure is how the best learning is done. The most meaningful work exists at the precipice of danger. Attempting to tackle something with a daunting degree of difficulty, straddling that ultrafine edge between competence and collapse.

Although it's a simple structure, I was responsible for every cut and screw and shingle. Every inevitable imperfection from my own miscalculation or mistake. But, this irreversibility added an invigorating amount of weight to the work and made it more meaningful in my eyes. Every step had to be considered carefully.

After all, only the things that are somewhat impossible to undo can be truly romantic.

Everything you do, especially every hard thing you do, covers over your reality with a fresh coat of paint. What you pay attention to, even the way you pay attention, changes. Since setting out to build a woodshed, every log cabin, wraparound porch, and sun-strewn trellis became an object of new fascination. How are they built? How wide are the beams? How many feet between floor joists? How is the roof supported? Nails or screws? Bolts or brackets?

I began to look at what I had previously only seen. In this, I rediscover how little I know about the world. How much wonder lays dormant, even in the most mundane things.

the build

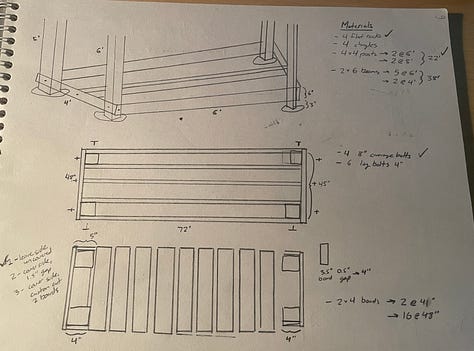

To begin, I spent a few weeks sketching different designs for woodsheds, copied out of a 1990s book on cabin construction. I dreamt of building a timber-framed chateau for our little logs, but I only had a few weeks to work and a small 4x8 foot space. However, I tend to think learning is accelerated by constraints. My focus was narrowed from building anything and everything, to building a specific structure.

I started a Pinterest board for inspiration and collected images of woodsheds, focusing on aesthetics and size. Once I narrowed in on a handful of particularly pleasant designs, I finalized my drawings, with precise measurements, and made a materials list.

It would be a 4x6 foot structure, with a slanted roof that opens outward, spaced siding to keep logs safely tucked in, but still allow for ventilation, and a sturdy 2x4 inch floor to hold a few hundred pounds of wood. The shed is somewhat overbuilt for its purpose, but I wanted to create something stronger and more magnificent than necessary.

The first few days were spent clearing out and hauling away old logs, leveling the ground, and digging little beds for four flat rocks where the main posts would sit. Then, day by day, the frame was built out, the siding latched, the floor finished, the exposed wood painstakingly stained, and the roof attached and shingled.

My brother lent a hand, which sped up and smoothed out the process. I've found if you work on interesting and ambitious things, people often want to help.

The crucial part of the build, where mistakes are most costly, was the foundation. If the frame was unlevel or spaced weird, that error would ripple through and throw off the whole structure. It's wise to work slowly in these stages. Perhaps it’s worth thinking about how this idea applies to much more than building sheds.

All wood used was spruce, except the pressure-treated 4x4 inch posts, purchased from a local family-owned lumber yard (cheaper than Home Depot or Lowes). The final cost, including the posts, siding, floor, bolts, and brackets came to $313.963. Initially, I wanted to shelter our logs with galvanized steel. Steel roofs last forever, whereas shingles must be thrown in a landfill after 25 years. Instead, I opted to use sheets of plywood and shingles we had laying around our toolshed. Buying environmentally friendly materials is good, but buying nothing is better.

The biggest surprise was how easy it was. Only a few months ago, the notion of building a shed was obscured by a vague cloud of impossibility. But all it required was a bit of planning, some beginner's skills, and plenty of careful attention.

I never understood agency until I just started trying things. Before, observing it in others, it looked like magic.

Developing basic competence in almost any domain doesn't require a ton of time. And luckily, you only need basic competence to start something, to strive. To make something beautiful or just a little bit better. Effort, by order of events, must precede success4.

I called it the Log Lodge. Partly for the snappiness off the tongue, but also because our wooden guests will only be staying there a short while.

an antidote to abstraction

Over the summer, I was trying to understand my increasing pull to the analog world. Why I've retreated to leather-bound books with crisp pages that smell of old paper, picked up an old Canon camera, spent days out in the deep woods. Reading Micheal Pollan's A Place of My Own was the intellectual equivalent of snapping the last puzzle piece into place.

Pollan is a writer whose working life "was conducted in front of screens at an ever-greater remove from the natural world". Growing up, his Dad never owned a toolbox. He didn’t even know how to swing a hammer. That is, until in his early 40's when he decided to build a writing cabin behind his home in rural Connecticut.

Like Pollan, I spend hours every day sitting in front of a screen or planted in a chair with a pile of books. It's the most fulfilling work I can currently envision for myself, but there are whole parts of me that it fails to address. For instance, my body.

At the end of the day, even if I'm diligent and disciplined, there isn't much, if anything, I can point to that I did. My efforts don't add anything to the physical stock of reality. Just a few thousand words on a glowing monitor.

There's something deeply unsatisfying about knowledge work: sometimes, it doesn't feel like real work5.

I think I've been looking for an antidote to the abstract nature of my existence in the dodgy world of words, where much of reality seems to slip through or entirely evade its net.

From teaching myself photography or cooking or carpentry, I've fostered an appreciation for the kind of knowledge that lives in the hands. Knowledge that can only be absorbed from patience and practice. Knowledge that can't be well-explained or even articulated, but felt. I think I've fallen in love with this dialect of embodied understanding that is developed within an ecology of "handwork, sweat, and a particular quality of attention that involves very little intellect, but all of the senses".

There's a real joy to working with physical, tactile things6.

I still enjoy inhabiting the intellectual domains and I think it's a mistake to shun them too harshly7. But, digital life in its excess becomes disembodied. This feeling of being a big floating head, an impenetrable film of frosty glass between you and reality. Like many people in their 20's, that's the exact ailment I feel most: this heady, introspective remove from the real world, frozen by constant consumption into an overly patient passivity. Spending my whole life waiting for it to start.

The Internet, despite its wonders, is an abstract and disembodied place. A "home page" is not homey, the "information highway" is not dreamy to drive down, and "electronic town halls" just plain old suck.

Hours spent working directly with the flesh of the world is the best antidote to abstraction8.

In admiration,

If you enjoy my work and want to help support future essays, you can become a patron and join our little but growing community:

Or if you’re not ready to become a patron and also savor the aroma of freshly ground coffee in the quiet hours of the morning—you could buy me a coffee.

👋 what i’ve been up to:

I finished building the Log Lodge and spent a few days splitting and stacking logs to prepare for the winter. I also built a smaller woodshed with 2x4's that sits on our back step near the door, to grab wood quickly in the cold months.

My brother and I drove four hours North to Killarney Provincial Park to hike the 80km La Cloche Silhouette Trail over 5 days. They're some of the oldest mountains on the continent, once taller than the Rockies but have eroded to ~600m elevation over the last 1.2B years. We met lots of beavers, a hefty porcupine, and a bear.

Back home, I've picked up some new projects (like building a floating bookshelf) and I'm doing a few festive things to celebrate Fall before I set off on my next adventure...

✍️ quote i’m pondering:

“You can easily judge the character of a man by how he treats those who can do nothing for him.”

— Malcolm Forbes

📸 photos i took:

September in Ontario.

As they say, “necessity is the mother of invention”.

They are a lazy solution, an egregious eyesore, and most importantly, a detriment to the dignity of the human spirit.

The same shed is $995 + HST + $300 for delivery from a nearby garden center.

But, my cost doesn't include screws and nails, stain, or anything used for the roof.

Watching Jerry Seinfeld's Duke Commencement speech this week, his emphasis on effort stood out. To cultivate a love for effort. Work is one of the only things that justifies itself in the attempt alone.

"Whatever you're doing, I don't care if it's your job, your hobby, your relationship. Make an effort.

Just pure stupid, "no real idea what I'm doing here" effort. Effort always yields a positive value. Even if the outcome of the effort is absolute failure of the desired result.

This is a rule of life.

Just swing the bat and pray is not a bad approach to a lot of things.

... The only two things you ever need to pay attention to in life are work and love. Things that are self justified in the experience. And who cares about the result?

Stop rushing to what you perceive as some valuable endpoint. Learn to enjoy the expenditure of energy, that may or may not be on the correct path."

An ideal, to me, is a synthesis of white-collar work and blue-collar hobbies. I think you need both to balance yourself out. (And no one in their right mind would pay me to fix or build anything for them).

I run and push up and pull up and swing kettlebells and stretch every day, besides the sabbath. But even exercise feels somewhat sterile and two-dimensional.

The farmer does not have time to work out. He has work to do.

Like software engineers on Twitter complaining about their work and fantasizing about moving to a farm.

Paraphrasing Pollan here. The words in the quotations are his.

I think a lot of creatives and people who, in general, live in their heads, will find themselves agreeing with the premise of this post. I think there gets a point where it feels extremely nauseating and even anxiety inducing if you spend all your hours locked in a room, dancing with theories and books and ideas and words and images but never with reality itself. And the doubts of whether one is doing real or fake work creep in. That’s what Paul Graham was getting at in this post: https://paulgraham.com/selfindulgence.html

But perhaps this is the exact reason why Nobel laureates have very contrasting hobbies to the kind of work that they do (read Range by David Epstein). For example, some Nobel winning scientists would spend a lot of free time playing an instrument. Because a hobby like that keeps them rooted in reality, as a kind of antidote to abstraction. And also, maybe it’s because the world of ideas and word and abstraction ceases to be useful once it’s devoid of any connection to reality. Reconnecting to the world might help the quality of your work in so many ways. Great writing!

You did a fine job of building the Log Lodge. You were methodical with research, drawings and studying. I dare say your writing is the same. In 1981 we lived in Auburn, Wa. We split five cords of wood with our neighbor. They were huge, the size of of telephone poles. My husband was the cutter/splitter and I was the stacker. It was very hard work.