My life became interesting when I began to focus on making things and stopped watching TV.

One gets an astounding amount of stuff done without a TV. Not that "getting stuff done" is the point of life, but more that there are so many interesting things to do.

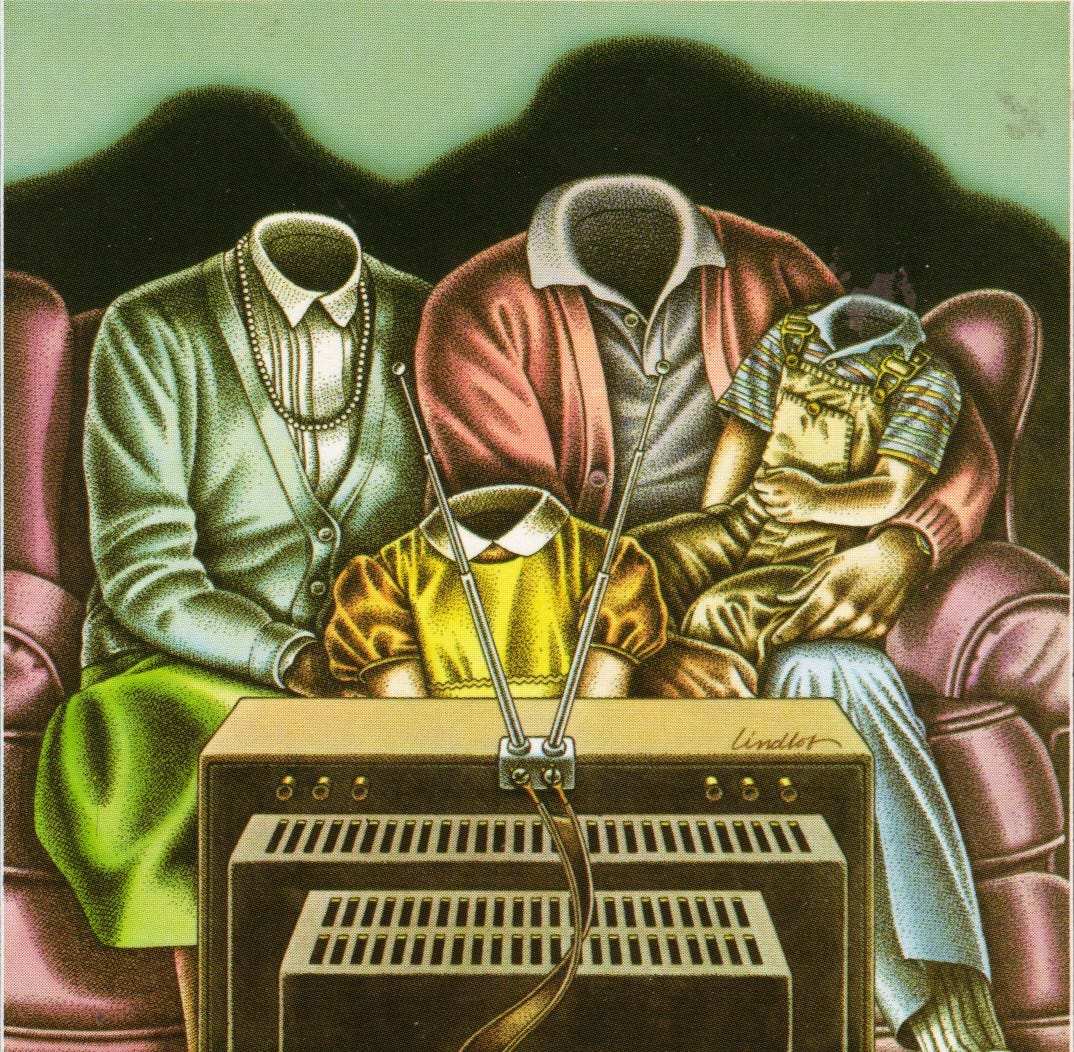

I think we've lost a basic expectation of nourishment from leisure. But only by stepping out of the frame of the last 100 years can we see how crazy and consuming it’s become. People used to build beautiful things, walk among the willows, shout stories at a local pub, or reflect before the fire. Now the national pastime is to sit inside, on the couch, in dim blueish light, and watch television. Even a cursory glance at the windows of a condo building at night confirms TV's grip on our culture1.

Yet I don’t think it’s revitalizing or even that relaxing.

I'd argue our brains are too smart to feel good about it. Instead, we're left with this permeating numbness. This piercing, anxious apathy that brews in the blood. A constant gnawing sense of having had, but lost, some infinite thing2. "Binge-watching shows is a modern anesthetic for a discontented life," my friend once told me on a phone call.

I think we should take our dissatisfaction far more seriously. I’m deeply troubled by the fact we don't.

Screens have decimated our attention spans to the point where we can no longer read ten pages of a book or deeply listen to someone express their concerns and commitments, let alone be with nothing but our thoughts. There's that line from Pascal: "All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone."

It is possible to distract yourself for every waking minute of your life and not even notice you're doing it.

Television is so pernicious because it never asks you to think. It only asks for all your attention. Television, as a medium, is one-sided. Speaker to listener. Pulpit to pew. Patrician to plebian. There's no window for response or conversation. This, I think, adds a subtle shade of passivity to how we see ourselves situated in the world. It attacks our agency: our capacity to act outside of the events that simply happen to us, our determination to make things happen. TV coats the mind with a film of inertia.

I don't know what frightens me more, the constant consumption of content that crushes us, or our endless ability to endure it.

Aldous Huxley prophesied in Brave New World that people will come to adore the technologies that undo their capacity to think, as they gorge their almost infinite appetite for distraction. While Orwellians said an iron fist would take away our liberties, Huxley knew we would do it to ourselves. We would welcome our oppression. Even fight to protect it. Huxley feared that what will ruin humanity will not be what we hate, but what we love3.

I, for one, have only been able to get any solid footing for this fight by standing on a foundation of cold truth: that it’s an addiction. An addiction to distraction as our culture collectively amuses itself to death.

Addictions, at root, are always acts of avoidance. Without TV, I’m forced to confront the gaping holes in my life. The fact that I sometimes put up a wall when I'm around family or the fact I don’t have as many friends as I used to. That I'm not a part of any kind of community or can’t consistently care about a single hobby to develop real competence. That I struggle to have faith in anything except my own exaggerated self-importance, burrowing into an unutterable inward isolation, becoming the lord of my own skull-sized kingdom.

Last summer living off-grid, I went two months without television. I missed the news and the Olympics and even the NHL playoffs. But instead of being bored, I was weightless. Days were spent building things, swimming in the ocean, lounging in the sun, laughing. Evenings were stretched out with long meals on the deck and longer card games, and sometimes just sitting quietly watching the dusk darken and gazing into the crystal bath of stars, shimmering in the gloaming4.

I read somewhere that people smoke because they want to die at least as much as they want to live.

Perhaps distraction works the same way. Perhaps people chain themselves to a screen because they want to numb at least as much as they want to feel.

Much to ponder,

If you want to get closer to me and my work, the best way is by becoming a patron of this newsletter. You’ll get some behind-the-scenes access to how I write and the chance to ask me anything, if I can be of service.

Thank you to everyone who has been generous enough to leave a few dollars in my digital tip jar. Recently, I’ve put all the money toward completing my Shakespeare collection.

👋 what i’ve been up to:

On Monday, I flew to Seattle for three days of an incredible leadership development course, called The Heart of Leadership, taught by Amba Gale. A pathway made possible by the insanely generous sponsorship of a mentor and friend.

Then, I came back to Canada, where I’ll be spending the next four weeks volunteering on a family-owned organic vegetable farm in the southern tip of the Okanagan Valley.

✍️ quote i’m pondering:

“It is easier to forgive an enemy than to forgive a friend.”

― William Blake

📸 photos i took:

September in Canada.

Technically I haven’t thrown out a TV since I don’t own a TV. And, as I'm told, it’s impolite to throw out someone else’s.

The reason why a TV must be thrown out is the same reason why junk food can never just be left in the cupboard.

Paraphrasing DFW here.

If you like this line of thinking, I’d recommend Neil Postman’s short, 337-word foreword to his book Amusing Ourselves to Death, a book on the “corrosive effects of television on our politics and public discourse”. It was a big influence on this piece.

The world contains an inexhaustible wealth of projects with meaningful rewards and people have more free time than ever. Lack of interesting things to work on is almost always a lack of imagination. All children know this.

There is a book called: Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business by

Neil Postman from 1985, where he talks about this specifically regarding what was then regarded as "TV".

But I believe "TV" is whatever invention we humans use to distract ourselves from dealing with the real world. It's no longer just the passive watching of televised programming like it was in 1985.

"TV" today is actually "social media".

I just moved into a new apartment, and my mum can't seem to wrap her head around the fact that I don't miss having a television. She often remarks, 'You're one of the few people without one,' as if I've evolved into some strange new human species.

I explained to her that for me, avoiding TV isn't about rejecting technology or entertainment; it's about using this time and mental space for creation. When I'm not passively absorbing content, my ideas can finally come out. So I would say that the absence of television isn't an emptiness; it's a deliberate choice to engage more actively with the world, to think, to read, to create. It's about choosing activity over passivity, which, as you've already pointed out, is exactly where television tends to nudge us.